Strength Training for Trail Running part two with Emma Wallace

Health and wellness coach Emma Wallace is a trail running enthusiast, often found exploring the local forest with her four legged companion, Cookie.

She practices as a sports specific strength and conditioning coach and has trained professional and everyday athletes in sports such as road running, CrossFit and boxing. Emma utilises the skills she learnt becoming an accredited British Weightlifting Association Instructor and has graduated in Sports Science & Human Performance with First Class Honors.

We had a great chat about the benefits of strength training for running, to improve trail running performance. We decided we should get together for a series of blogs to help explain the why and the how of strength training for trail running.

Here’s part 2 to explain the “How?”

Why should we implement strength training for running into our training?

In our previous blog we explored the benefits of strength training for trail running. After delving into scientific literature, it became apparent that strength training is a tool we can utilise to improve an athlete’s “running economy”. This term refers to the energy demand for a given velocity, which is often compared to the rough equivalent of a cars fuel economy.

The main reason behind this is that strength training creates tendon stiffness, which produces “free energy” when the tendons recoil. This energy can be utilised to propel an athlete forwards, much like a thick elastic band. Comparatively, relying on our muscles to metabolise carbohydrates and lipids for energy is a more lengthy and costly process.

It is the number of sets, number of repetitions and % of maximal load that really contribute to the effectiveness of strength training. It is also useful to have some basic knowledge of the anatomy that is used in running so that the correct exercises can be selected. The lower body is important for obvious reasons, so let’s look at some of its key kinetic functions.

What do our bodies do whilst running?

During running, the calves control ankle movement with a lengthening (eccentric) contraction during dorsiflexion (shock absorbing phase and the action of raising the foot upwards towards the shin). The Achilles tendon, attached to the ankle, releases energy when it shortens in plantar flexion (the movement in which the top of the foot points away from the leg and pushes off the ground). This pattern is often referred to as “the stretch shortening cycle” and takes place in other areas of the body, for example, the knee joint.

When a runner makes contact with the ground, the knee is slightly bent in a semi squat. This knee flexion is absorbing ground forces, then very quickly re-extending to toe-off and propel the runner forwards. Similarly, the knee joint and Achilles tendons stretch and shorten during small jumping movements on technical trail terrain. These movements occur at unimaginable speed, around 200 milliseconds and even quicker as pace increases. When there in an increase in pace, the need and time for knee flexion reduces. This increases the demand for stiff quadricep tendons to create rapid ‘free energy’ to be used on extension.

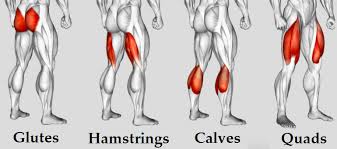

Which muscles should we focus on?

The quadriceps and calves are important to include in a strength program, but the use of the gluteals and hamstrings should not be neglected. By including these muscle groups, not only do we create a balanced program, but we also strengthen two muscle groups that are often considered the “power houses” behind running.

Quad dominant exercises include squats and lunges whilst hamstring dominant movements include deadlift variations. All of these movements target gluteals whilst the calves are best isolated with calf raises.

As running is a unilateral sport it makes perfect sense to also include single leg work, for example step ups, leg extensions and leg curls.

The core is challenged during the larger compound exercises if braced correctly. To avoid confusion we will not program additional core work in this blog, however by all means include it into your plan if you do not already.

How “Heavy” should we lift?

Many studies have shown that heavy weight training is the most beneficial way to increase tendon stiffness. In the context of running training, heavy weight training means an athlete lifting loads of 75-90% of their one repetition maximum (1RM).

1RM’s can be defined as the maximal weight an individual can lift for one repetition with correct technique. Sets of 3-5 and repetitions of 3-6 have shown best results for developing strength and tendon stiffness.

How do we calculate our 1RM so we can calculate the correct weight to lift?

How to calculate a 1RM is a discussion in its own right. Techniques depend on which scientific literature is used for reference. To grasp the basics of the concept, the following session is suitable for an athlete with 6- 18 months of lifting experience to calculate their 1RM.

Rest 3-4mins between each set.

Warm Up

- 10 reps with only the barbell.

- 8 reps with a barbell + light weight.

- 6 reps with a barbell + moderately heavy weight.

- 5 reps with a barbell + heavier weight.

Test

- 3 reps with a barbell + heavy weight (assuming correct form.)

- 3 reps with an increased heavy weight.

- Repeat until form slightly deteriorates or RPE (rate of perceived exertion) is between 9-10.

Once you have found your maximal load at 3 reps, multiply that weight by 1.08. This will calculate your estimated 1RM.

For example, if an athlete has stated an RPE of 9 and has slightly deteriorating form for 3 reps on a back squat of 50kg, their estimated 1RM is 54kg. The athlete would then look to program squats at 75%-90% of this load: 40.5kg to 48.6kg.

However, if an athlete is new to strength training then the concept of working with a 1RM may become void. The use of bodyweight exercises alone may be enough to create the desired stress on the body (for example, some people are unable to do a bodyweight pull up, therefore body weight is above a 1RM and there is no need to add additional load to this exercise).

Much like how a person new to running need not and should not complete a trail ultramarathon straight away, a beginner in strength training should not load up a barbell if they cannot perform body weight movements. However, regardless of whether an athlete is a beginner or advanced lifter, sets of 3-5 and repetitions of 3-6 have shown best results for developing strength and tendon stiffness.

How should we structure our weight training?

In the 2016 Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, Beattie et al found that including just two sessions of strength training per week significantly improved maximal and reactive strength qualities. “Running economy” and VO2 max also improved without increasing muscular hypertrophy.

With this evidence, an understanding of the muscles and tendons used, as well as knowledge of sets, reps and % of 1RM, a basic plan can be formulated.

With all these exercises, they must be performed correctly with good form. This is not only to ensure that you get the most benefit from them, but also to make sure you don’t injure yourself.

We encourage you to explore the many available resources on the correct techniques. Feel free to get in touch with me (Emma) via my Instagram below, contact another Personal Trainer or even ask at your gym.

Here’s an example for Week 1 of a strength cycle:

Strength Session A:

- Back Squat 3×5 (80% of 1RM.)

- Romanian Deadlift 3×5 (80% of 1RM.)

- Lunge 3×5 (80% of 1RM.)

- Single Leg Calf Raise 5×3 (75% of 1RM.)

Strength Session B:

- Front Squat 3×5 (80% of 1RM.)

- Conventional Deadlift 3×5 (80% of 1RM.)

- Box Step Up 3×5 (80% of 1RM.)

- Seated Calf Raise 5×3 (75% of 1RM.)

How do we progress week on week?

Just like with running programs, it is important to add small progression each week in order to benefit from physical and neural adaptations. For a beginner, it may be simplest to add more sets and reps but for a runner with more experience in strength training, increasing the weight based on % of 1RM is a great way to challenge the body.

Here’s an example of how the first aforementioned strength session could be progressed for a beginner and for an advanced athlete.

Beginner Progression of Strength Session A:

- Back Squat 4×5 (80% of 1RM)

- Romanian Deadlift 4×5 (80% of 1RM)

- Lunge 4×5 (80% of 1RM)

- Single Leg Calf Raise 5×4 (75% of 1RM)

Advanced Progression of Strength Session A:

- Back Squat 3×5 (82% of 1RM)

- Romanian Deadlift 3×5 (82% of 1RM)

- Lunge 3×5 (82% of 1RM)

- Single Leg Calf Raise 5×3 (77% of 1RM)

Strength training cycles typically last 8-12 weeks with a de-load week incorporated during or after. This de-load week gives the body time to adjust to the additional demands placed upon it.

So, there we have it, the science behind strength training and a basic tool kit to create a strength training program that’ll improve your trail running.

All that is left to do now is to purchase a set of weights or hit the gym (with covid-19’s discretion of course…).

Follow me at https://www.instagram.com/emmawallacecoach/ and feel free to drop me a message with any questions.

Happy lifting!