Strength Training for Trail Running with Emma Wallace.

Health and wellness coach Emma Wallace is a trail running enthusiast, often found exploring the local forest with her four legged companion, Cookie.

She practices as a sports specific strength and conditioning coach and has trained professional and everyday athletes in sports such as road running, CrossFit and boxing.

We had a great chat about the benefits of strength training to improve trail running performance. So we decided we should get together for a series of blogs to help explain the why and the how of strength training for trail running.

Here’s part 1 to explain the “why?” behind strength training in trail running.

Every type of runner, whether a professional athlete, local Starva hero or ‘couch to 5ker’ wants to improve their performance. We all want to make every run feel faster and stronger for the least amount of additional effort. Well, luckily this can be achieved without the need of expensive ergogenic aids or fancy footwear and even without adding hundreds of extra miles on the road, track or trail.

The training protocol in discussion here is ‘strength training’. A form of resistance training. The importance of strength training as a tool to protect against injury is no secret, it has been championed for years. More recently it has been unequivocally approved by anecdotal evidence and scientific literature as a means to enhancing performance. Specifically in relation to running economy (a term we will go on to explain).

Following a number of studies, sports scientist Timothy J Suchomel and his cohorts summarised the significance of strength training in a recent scientific review article. ‘It appears that there may be no substitute for greater muscular strength when it comes to improving an individual’s performance while simultaneously reducing their risk of injury.’. Suchomel goes on to conclude, ‘Practitioners should implement long-term training strategies that promote the greatest muscular strength within the required context of each event’.’

So then, alongside the long runs, the hill repeats and the intervals. Strength training needs to take its place in any trail runner’s program. But before diving into a new strength training routine for trail running, let’s investigate what strength is, why it is important and how it effects performance variables? Because the more knowledgeable we are about our training and about our bodies, the better athlete we can become.

What is strength?

So what is strength? Scientists have defined muscular strength as the ability to exert force on an external object or resistance (Oyvind Storen et al., 2008). This can mean different things depending on the context. For example, muscular strength in rugby can refer to how an athlete exerts forces against an opponent, in field athletics it tends to be how an athlete projects an object (such as shotput or discus). In our example, trail running, it is how a runner exerts force to manipulate their own body mass. Regardless of the sport in question, whether that be in off-road triathlon, mountain bike racing or straight out trail running, a limiting performance factor can always be an individual’s muscular strength.

The science behind trail running

Due to the distance covered in trail running events, the sport is considered 80-90% dependant on aerobic metabolism. In layman’s terms aerobic metabolism is the way our body creates energy through the use of fuel sources (such as carbohydrates) and in the presence of the oxygen we breathe in.

Aerobic running performance for trail running is dependant on three factors:

1. Our VO2 max (the maximum amount of oxygen we can consume).

2. Our lactate threshold (the intensity of exercise at which lactate begins to

accumulate in the body faster than it can be removed).

3. Our running economy (the energy demand for a given velocity). This is often compared to the rough equivalent of a cars fuel economy.

Number 3: Running economy, is notoriously a difficult aspect of trail running to improve, which is where strength training comes into its own.

One clear example of this is Oyvind Storen and associates’ 2008 paper, ‘Maximal Strength Training Improves Running Economy in Distance Runners.’ In this study, 17 well-trained athletes were randomly assigned into either an intervention or a control group.

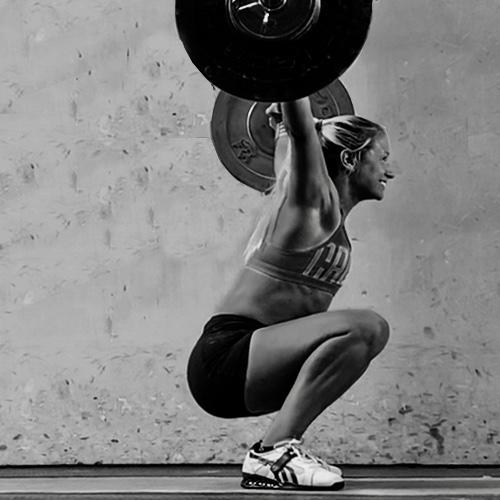

The intervention group performed half-squats, (four sets of four heavy repetitions), three times per week for 8 weeks, as a supplementary routine to their normal endurance training whereas the control group continued their normal endurance training over the same period.

The results speak to for themselves with significant statistics for the intervention group…

There was a 5% improvement in Running Economy in addition to a 21.3% improvement in time to maximal aerobic speed (the time taken to reach the minimal running velocity at which our VO2 max occurs). And what makes this even more interesting is that no changes were found in body weight as runners, triathletes, ultramarathoners and other endurance athletes are often sceptical about hitting the weight room because of potential muscle and weight gain.

However, the scientists behind this study explain how the resistance work likely increased neural adaptations rather than muscular hypertrophy (muscle growth). It is these neural adaptations that positively impacts running economy (our key performance target).

Storen et al., believe that strength training (and specifically in their study, heavy squats) increases muscle–tendon stiffness. Tendon stiffness is of significance here as increased tendon stiffness has been found to be responsible for the store and release of energy.

Tendons stretch and recoil under force (when your foot hits the ground) they can be utilised for elastic energy exploitation through the recoil function of tendon. This function is an asset to runners as it can be considered ‘free energy’ due to the tendons producing force without active, muscular contraction which is taxing on the body.

Think of stiff tendons work like thick elastic bands, which when pulled, recoil at a faster speed than thin stretchy elastic bands. A stiffer tendon – as a result of strength training – will produce more ‘free energy’, a quicker recoil time and a reduced contact time or ‘springier step’. It is this that enabled the athletes in Storen’s intervention group to improve their running economy, the ability to powerfully move forwards with each step…

We can contrast this against Storen’s control group, who still had lax tendons. These athletes had to work harder as the increased stretch created a longer ground contact time and inefficient force absorption, ultimately resulting in a lower running economy.

Strength Training = Stiff Tendons = Free Energy.

So in conclusion, strength training is a variable that we can manipulate to improve an athlete’s running economy. One reason behind this the fact that strength training creates tendon stiffness. Tendon stiffness produces ‘free energy’ for an athlete to utilise as a ‘springier step’ enabling them to move forwards with more power at little energy expense from our larger muscles groups.

As shown in Storen’s study, squats are a fantastic way to train towards stiff tendons and free energy, but they are not the only exercise we can add to our arsenal.

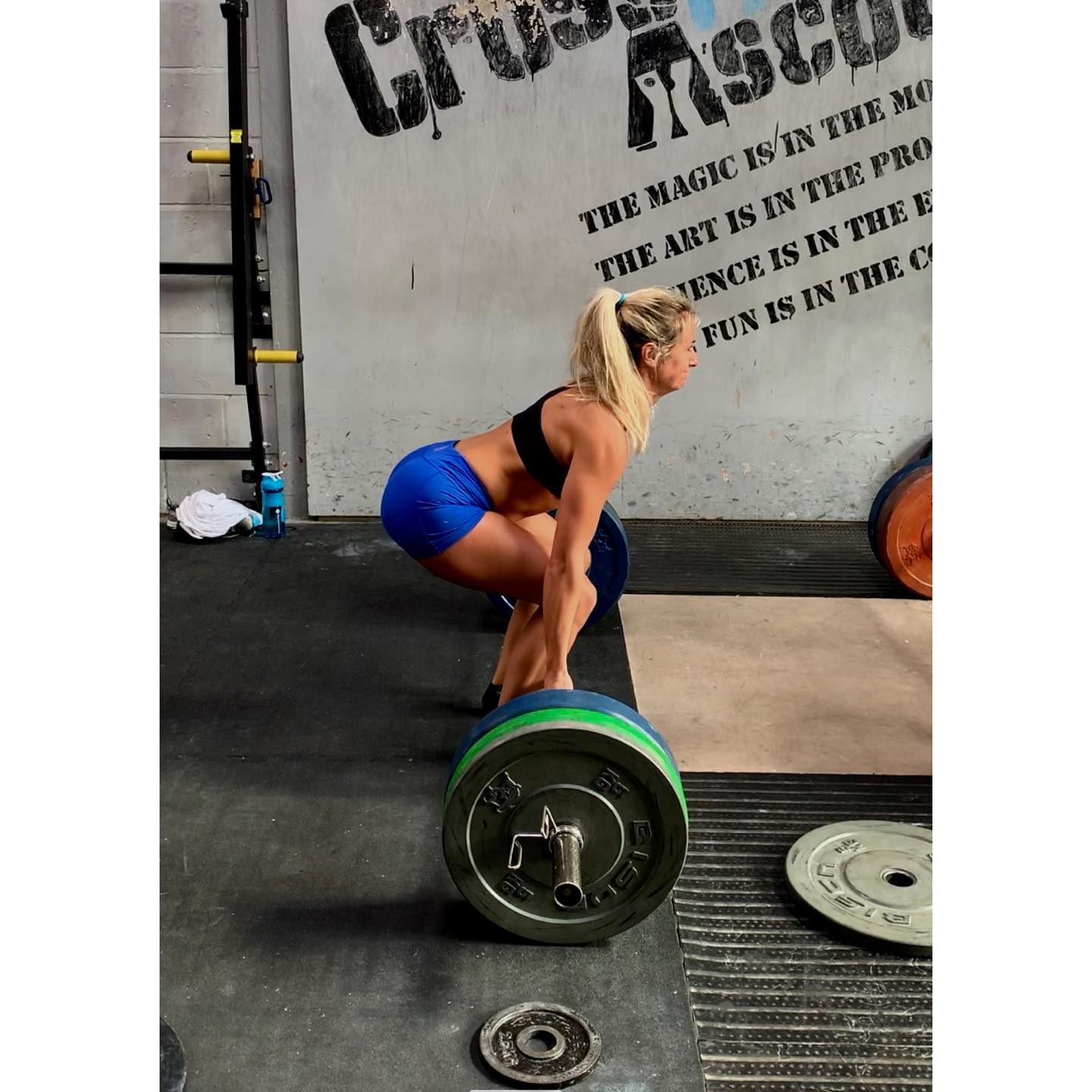

Classic gym movements such as deadlifts, lunges, bridges and leg press can all develop running specific tendon strength. It is the number of sets, number of repetitions and % of maximal load that really contributes to the effectiveness of the training protocol and this is what we will delve into on our next blog.

You can follow Emma on Instagram at @emmawallacecoach so if you’d like some help with strength and conditoning for trail running then get in touch.

Give this a share and keep your eyes out for part 2 coming soon.

We’ll see you all at a TrailX event soon.